This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

A malignant biliary obstruction (MBO) occurs when there is a blockage of the bile outflow towards the du¬odenum due to a malignant tumour. The most com¬mon tumours that cause MBO with direct invasion of the biliary tree are pancreatic carcinoma and cholan¬giocarcinoma. The biliary tree may also be blocked from tumours that cause external compression, such as enlarged hilar or ampulary lymph nodes or in some cases of hepatocellular, gastric or gallbladder cancer. Surgery is the treatment of choice if the disease is at an early stage and adjacent structures are not infiltrat¬ed. Otherwise patients will receive palliative treat¬ment for quality of life improvement. Percutaneous transhepatic image-guided biliary interventions offer a minimal invasive approach that decompresses the blocked biliary system and have an established role in the management of both operable and inoperable patients with MBO. A variety of devices and techniques have been de¬veloped for this purpose, including the use of internal and external drains, plastic, bare metallic and covered metallic stents, biopsy forceps and unilateral or bilat¬eral, one- or two stage- approach. The purpose of this review article is to offer a global overview of the in¬terventional radiology role in such patients and to dis¬cuss the latest developments.

The tumours that may lead to malignant biliary obstructions (MBOs) are mainly adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma [1]. Other tumours that may lead to malignant jaundice are ampulary, gallbladder, and hepatocellular carcinoma and lymph node strictures from gastric, pulmonary, breast and oesophageal cancer. When malignant jaundice occurs, the normal bile flow towards the duodenum is blocked. Although the complete cholestasis mechanism is not fully interpreted, the lack of bile in the duodenum results in a systemic inflammatory reaction due to release of cytokines that targets specific organs hence leading to multi-organ failure. The deranged liver function leads to Kupffer cells dysfunction and the lack of bile in bowel increases the membrane permeability and reduces the bowel bacterial barrier, so promoting bacterial migration, initially to the portal and then to the systemic circulation [2-4]. If this situation is not corrected, uncontrollable sepsis occurs very quickly in the majority of cases.

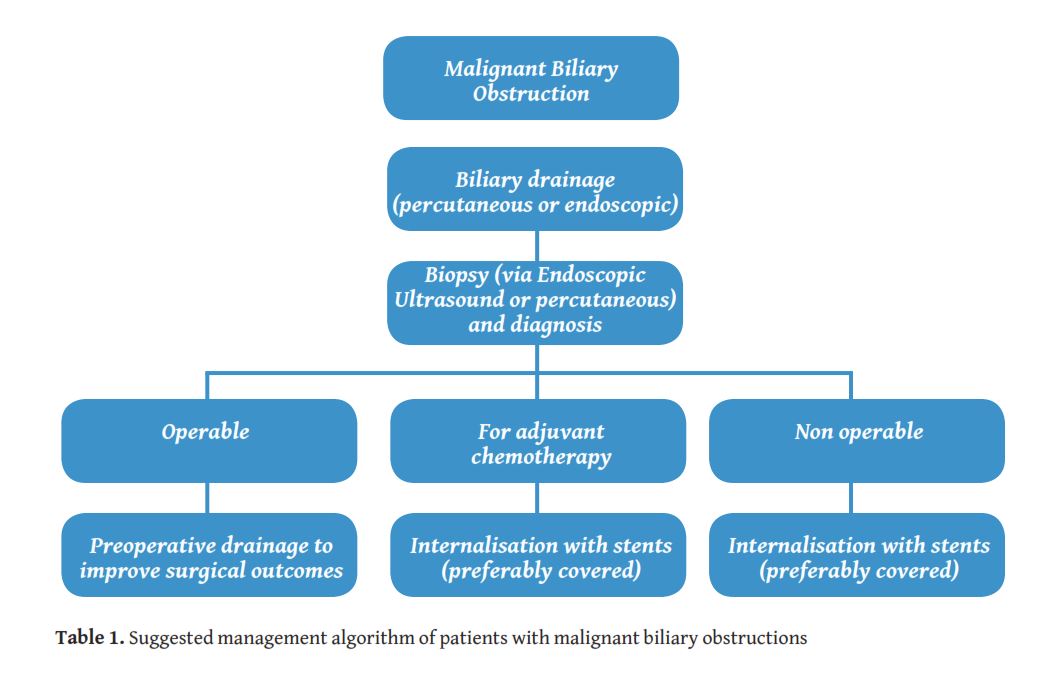

Patients with a MBO would either be considered operable or inoperable according to the stage of disease at diagnosis. Endoscopic drainage is usually the first approach in most of the centres. However this is not always technically feasible, particularly for lesions located proximally to the liver hilum [5]. Furthermore, when preoperative drainage is required there is an increased risk of infectious complications with the endoscopic approach [6]. The main contraindications for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are the presence of an oesophageal stricture, gastric volvulus, bowel perforation, unstable cardiopulmonary status that would prohibit patient to be positioned supine and history of previous bowel surgery with change of the anatomy (Billroth II or Roux-en-Y loop). Therefore percutaneous transhepatic drainage access should be considered as the most appropriate treatment option [7]. Once the biliary tree is decompressed and biopsy of the underlying lesion is obtained, a multidisciplinary team decides on whether to proceed with surgical resection or palliative treatment. In the case of palliative approach, internalisation of the drains with the use of stents is required in order to reduce infection risk during chemotherapy. Stents ideally need to be patent for the whole patient’s life span, in order to avoid treatment interruption or re-intervention for cholangitis. The management algorithm of a MBO patient is shown in

Initial imaging approach of MBOs is performed with trans abdominal ultrasound (US) that is expected to detect the dilated bile ducts and the presence of possible intrahepatic deposits. US is quick, accessible and of low cost. However some pitfalls may occur in the case of obese patients, when there is bowel interposition or in the case of paralysis of the right hemidiaphragm.

Computed tomography (CT) is usually performed not only to delineate the stricture but also to assess the presence of intrahepatic and distal metastatic deposits. A triple phase CT scan is usually recommended for characterisation of the malignant stricture, even though malignant biliary tumours are not expected to be enhancing avidly in the arterial phase. Adding a late contrast phase (6-15 min post injection) appears to increase the sensitivity of detection of adenocarcinomas [8].

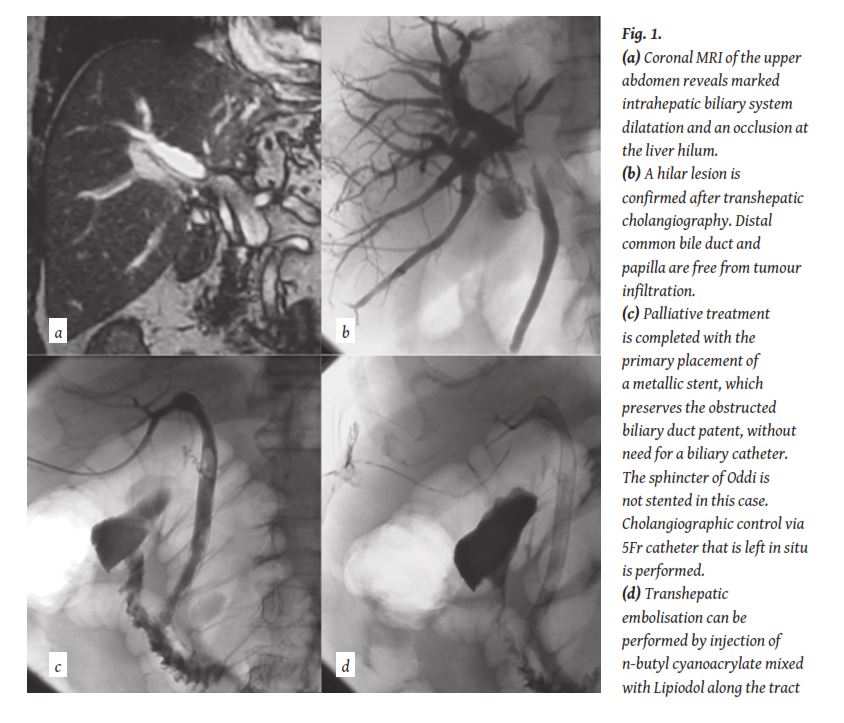

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays also an important role in the diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures, particularly if combined with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP); the latter is a T2-weighted fast-spin echo sequence applied with prolonged effective echo time (>240 milliseconds). The signal from static fluid (biliary tree) is enhanced and the signal from the surroundings structures is suppressed (

Malignant strictures involving the hilum are classified using the Bismuth-Corlette classification system based on the extension of the stricture into the intrahepatic ducts [10]. Bismuth type I strictures involve the proximal common hepatic duct and spare the confluence between the left and right ductal systems; type II strictures involve the confluence and spare the segmental hepatic ducts; types IIIa and IIIb involve either the right or left segmental hepatic ducts, respectively; and type IV strictures involve the confluence and both the right and left segmental hepatic ducts.

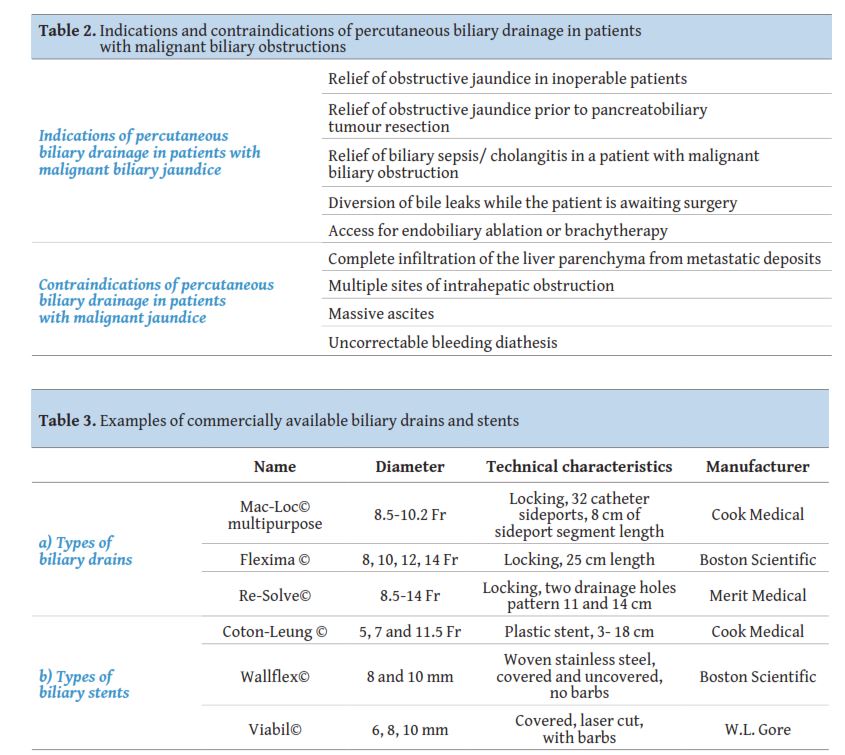

The main indication for percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in a patient with a malignant biliary stricture is the elevation of bilirubin from a mechanical cause. The procedure may be performed on an emergency basis if jaundice is combined with cholangitis and sepsis. Contraindications are mainly technical and are usually relative like i.e. the coagulation status of the patient or the presence or not of ascites, with the exemption of complete infiltration of the liver parenchyma from widespread metastatic disease (

Assessment of the coagulation status of the patient is of paramount importance prior to the procedure. In case of deranged clotting, blood products (vitamin k, fresh frozen plasma or platelet transfusion) may be administered. In case of presence of ascites, percutaneous drainage may be performed prior to accessing of the biliary tree. The procedure is usually performed under local anaesthesia (lidocaine 2%) and conscious sedation using 1-8 mg of midazolam and 50-200μg of fentanyl. Antibiotic prophylaxis (i.e. with cefuroxime 750 mg) may be administered before the procedure and continued for up to 5 days after the procedure according to the operator’s preference.

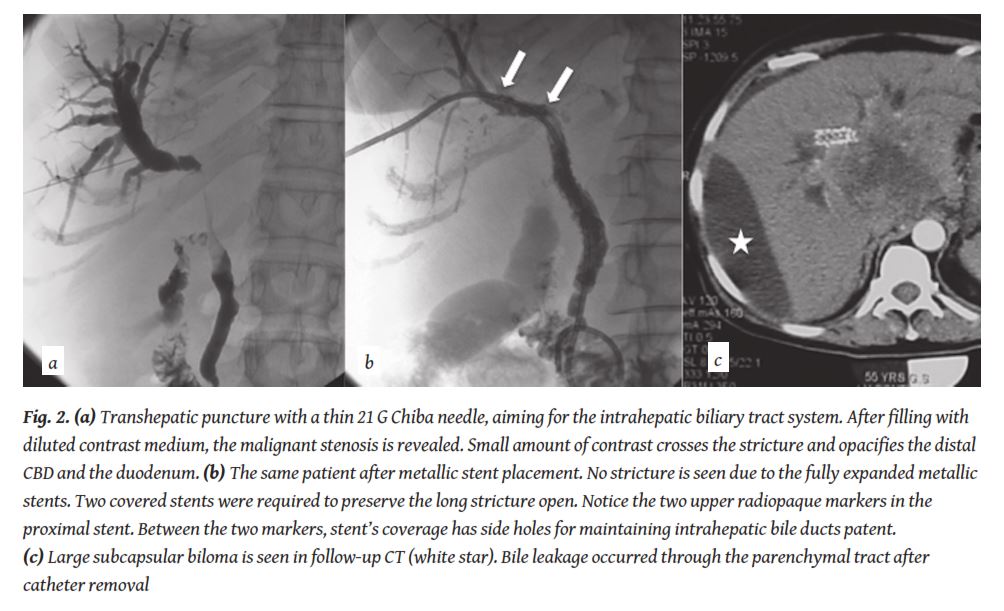

Percutaneous approach is performed by a transhepatic puncture with a rather thin (21-22 G) Chiba needle under US or fluoroscopic guidance. When access to a bile duct is obtained a minor amount of diluted contrast is usually injected to confirm correct position. Okuda et al. first described the fluoroscopically guided technique, in 1974 [11]. When the thin needle was positioned in the biliary system a cholangiogram was performed and a second puncture followed to a duct that was considered adequate in terms of angulation and size. The second puncture was performed with a 5 Fr needle catheter and a 0.035” inch wire was advanced in the biliary tree. With the use of US guidance, once the thin needle is in the biliary system a 0.021” inch wire is advanced in the biliary tree. The system is upsized to 6 Fr without the need of a second puncture in this case. When the 6 Fr catheter is advanced a cholangiography is performed with diluted iodinated contrast (

In case of opacification of multiple obstructed bile ducts, the operator should try to drain as many of the opacified ducts as possible in order to avoid bacterial contamination and post procedural contrast related cholangitis [13].

In the case of MBOs, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) follows in order to decompress the obstructed bile duct system [14]. The drainage of the bile ducts is usually performed with a small 8 Fr plastic multi-hole pigtail catheter. In the cases where the lesion has not been biopsied or in the case where the biliary tree is infected, external drainage catheter placement is suggested. The catheter is secured to the skin with sutures. Self-locking catheters are preferred in order to minimise the dislocation risk. In cases of complex hilar strictures, placement of multiple external biliary catheters may be necessary to achieve complete drainage. The types of available drains are described in

Biopsy of the lesion may be either obtained with endoscopic ultrasound - guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) or with the use of endobiliary forceps. EUS-FNA is effective in obtaining cytological samples for Bismuth I-II lesions, however for hilar lesions this access is less effective [15, 16]. In addition, the cytologic sample may not always be diagnostic and core biopsy of the lesion may be required. Endobiliary biopsy may be obtained with theuse of biopsy forceps overcoming the problem of inadequate sampling that is encountered with FNA [17]. The forceps may be advanced either endoscopically or percutaneously. In the case of percutaneous insertion a 7Fr sheath is used as access and a security wire is used and placed across the stricture. The forceps are placed on the side of the wire and usually 3-4 samples are obtained and placed in a formalin suspension.

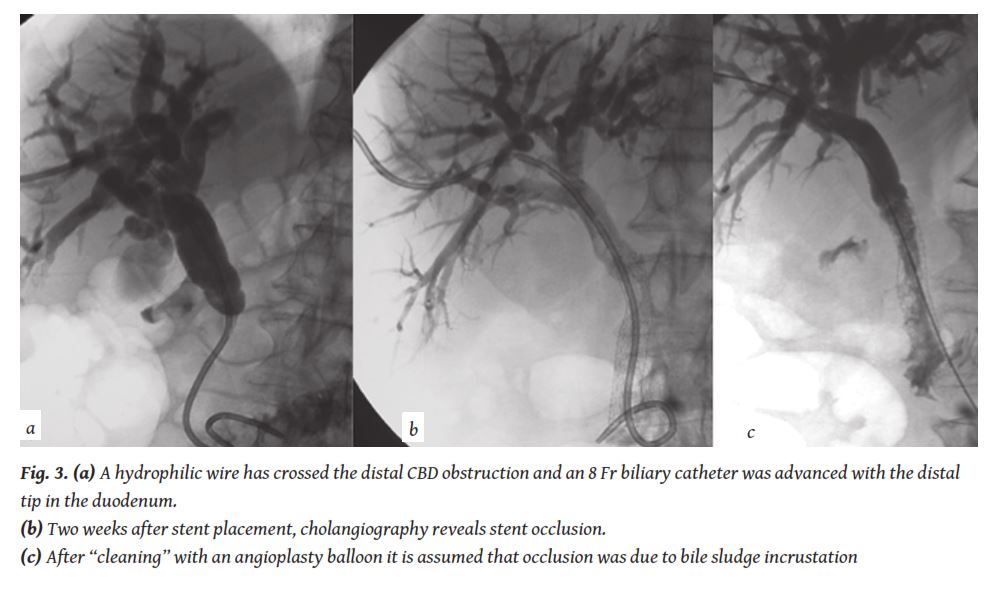

If there is already confirmation of malignancy and there is intention to proceed with a stent the obstruction can be crossed with a hydrophilic wire and the percutaneous biliary catheter can be pushed through the stenosed /obstructed duct, so that bile is draining both internally towards the duodenum and externally (internal- external drainage) (

5. Use of biliary stents

In case of inoperable tumours, internalisation of the drain is required in order to be able to either administer palliative chemotherapy or to offer a satisfactory quality of life [18-20]. This is achieved with the use of stents that may be plastic, bare metallic or covered metallic (

Metallic biliary stents have been proved as the best palliative treatment of non-resectable malignant obstructive jaundice, allowing longer patency rates than plastic endoprostheses [21]. The technique is safe, with a high technical success rate of over 97% and low complication rate [22, 23] and procedure related mortality is reported between 0.8 and 3.4%. Early complications rate within the first 30 days is about 2% while the late complications rate can reach 16% [23]. Mean overall primary stent patency is reported 120 days, but mean overall secondary stent patency is 242.2 days [22].

An integration process accompanies the deployment of metal endoprostheses within the biliary tree into the surrounding malignancy, which after a period leads to the formation of tissue through the stent’s struts that finally blocks the stent. This is the so-called “tumour ingrowth”. Ingrowth is the result of tumour growth but also of the accumulation of biliary sludge and bacterial biofilm. The motility of bare stents plays a crucial role on the latter aspect of ingrowth as “fractures” of the stents occur and lead to dysfunction. This effect occurs more frequently with laser cut metallic stents therefore the use of woven stents is suggested.

The malignant proliferation can sometimes occur in the proximal end of the stent and not through the mesh. This is called “tumour overgrowth” and also gradually blocks the stent lumen [24]. In such cases, patient requires new percutaneous intervention that leads to placement of a second stent through the occluded stent. In some cases stent occlusion is due to bile sludge and needs “cleaning” with a simple angioplasty balloon (

Hausegger et al. [25] in the early days of use of metallic stents in the biliary system analysed the histological changes after the deployment of stainless steel endoprostheses in the biliary tree for the treatment of malignant biliary disease. In fourteen cases histological examination was performed after autopsy and in one case a surgical specimen was analysed after tumour resection. In the analysed specimens, the stent was inserted in a period ranging from 5 days to 21 months. For the initial period of the first 15 days, histology revealed that the cuboid epithelium of the biliary tree is completely destroyed in the areas that were in contact with the stent. There were moderate inflammatory changes in the sub mucosa with minor lymphatic infiltration and oedema. The internal layer of the stent was covered by non-specificgranulomatous tissue. The fibrous tissue and the tumour were displaced. No tumour cells were recognised within the biliary tree lumen and no signs of acute inflammation were noticed. In the period between the 2nd and the 12th month the endoprosthesis was gradually integrated to the surrounding tissue by a layer of granulomatous tissue and tumour ingrowth. In a similar study Boguth et al. [26] describe similar histological changes that occur in the first 3 to 6 months and lead to the occlusion of the bare metallic endoprosthesis. Ingrowth through the mesh of the bare stent occurs in all patients that survive more than 6 months and re-intervention is usually required. The patients may present with cholangitis and a new procedure and a new stent placement is usually necessary to resolve the situation.

There is usually a difference in timing of clinical expression of symptoms that is related to the location of the tumour. Intrahepatic lesions tend to give symptoms later than extrahepatic ones. This is due to the fact that the only symptoms expected are those related to the malignant obstruction of the biliary tree and in case of intrahepatic tumour, there are several collateral drains that may be used until complete occlusion occurs [27].

In order to reduce stent’s dysfunction from tumour ingrowth, covered metallic stents were developed in the last decade. Various authors tested several coverage materials with a different range of results [27]. The initially used covered stents were “home made” by applying a coverage membrane on the available bare stents. Saito et al. in 1994 used biliary Gianturco-Roesch Z-stents covered with a Gore-Tex membrane [28] and reported satisfactory medium- to long-term results in a study of six patients. Thurnher at al. reported in 1996 their experience with the first type of covered Wallstents [29]. The coverage was a 0.015 mm thick polyurethane membrane that was also used from Rossi et al. in 1997 [30] and Hausseger et al. in 1998 [31]. Both investigator groups reported that the 0.015 mm polyurethane membrane was eroded from tumour and gastric juice. Similar results were also presented from Kanasaki et al. in 2000, where nitinol Strecker stents were used with the same coverage [32]. A 0.035 mm polyurethane membrane was used in homemade covered Gianturco-Roesch Z-stents and spiral Z-stents from Miyayama et al. in 1997, with better results [33]. Han et al. reported a 71% patency at 20 weeks using a 0.030 mm thick polyurethane membrane in covered Niti-S stents [34]. Isayama et al., using 0.040-0.050 mm thick polyurethane-covered Wallstents, did not report tumor ingrowth [35] and presented even improved results with a 0.050-0.060 mm polyurethane membrane using covered Diamond stents [36].

During the last ten years, covered stents with a coverage membrane from expanded poly-tetra-fluoro-ethylene/ fluorinated-ethylene-propylene (ePTFE/FEP) were developed and are available in the market (Viabil©, W. L. Gore & Associates, Flagstaff, AZ, USA) [24]. Randomised controlled trials were performed with the use of such covered devices that have shown the superiority of these covered stents in comparison to uncovered stents in specific patient population

Covered stents are not suitable for all patients with malignant jaundice. They have to be reserved for patients with a reasonable expected survival and not used in the case of advanced disease [39]. Furthermore, anatomical features have to be taken into consideration including the stricture site, location and patency of the intrahepatic, cystic and pancreatic ducts. Usually, only Bismuth type I strictures are suitable for covered stent placement, whereas specific covered stents may be placed in some cases of type II. The covered portion should not be advanced in the intrahepatic ducts in order to avoid cholangitis. For this purpose, covered stents with side holes have been developed. The “holed” region does not prevent tumour ingrowth and it is also not extending proximally enough to prevent tumour overgrowth as a bare stent would. Nevertheless, side holes permit placement in anatomically complicated cases avoiding cholangitis or cholecystitis. The same principal should be followed for the cystic duct but less for the pancreatic, since pancreatitis may less frequently occur and the location of pancreatic duct is not a true limit in stent placement.

Stent placement can be performed as one- (so called “primary stenting”) or two- (or more) step procedure. The factors that would influence the type approach are multiple but mainly consist of the presence or not of diagnosis of malignancy, the presence or not of biliary sepsis and technical issues such as intra-procedural bleeding or bile leak.

If a more than one step approach is decided then a biliary drainage catheter may be left in situ for 1-2 weeksbefore a stent is inserted. Adam et al. [40] introduced the concept of “primary stenting” in 1991 (

In the past years, there was discussion about the usefulness of bilateral versus unilateral lobe drainage and stenting. In case of bilateral drainage, stents may either be positioned by puncturing separately the right and left side ducts and catheterising separately the CBD (Y configuration), or may be placed from a single side puncture after catheterising the other side ducts and the CBD form the same side (T configuration). There is still a degree of controversy as to whether partial or complete biliary drainage should be done. Inal et al. [42] studied 138 patients with hilar malignant strictures that received unilateral or bilateral stenting. Only patients with type IV lesions appeared to benefit from bilateral stenting, whereas for those with Bismuth type II and III there was no benefit in terms of patency. Although the cumulative stent patency seemed to be better after bilateral than unilateral drainage approach, there is, based on the available literature, not enough data to support bilateral drainage for malignant hilar obstruction [43]. Older and recent studies show that partial-liver drainage achieves results as good as those after complete liver drainage with significant improvements in quality of life and reduction of the bilirubin level [22, 44, 45]. Therefore the insertion of more than one stent would not appear justified as a routine procedure in patients with biliary bifurcation tumours.

Another frequently asked question was if we should stent the sphincter of Oddi in every case, even if the tumour is ending higher than the level of the papilla. A study performed in 2001 showed that in patients with extrahepatic lesions lying higher than 2 cm from the papilla and with a relative poor prognosis (<3 months), due to more advanced disease or to a worse general condition, the sphincter of Oddi should be also stented in order to reduce the post-procedural morbidity (

Bare self-expandable metallic stents have a mean patency of approximately 6-8 months and this is superior to what the plastic endoprostheses offer (

What is of interest is the comparison between uncovered and covered metallic stents. ePTFE/FEP covered stents were used in two randomised trials published in the literature. In the first trial [38], covered stents were directly compared with uncovered in patients with Bismuth type I cholangiocarcinoma. Sixty patients (36 men and 24 women, with age range 46-78 years) were randomised with the use of a sealed envelope for the placement of a covered or a bare stent. In 21 cases the tumour also infiltrated the cystic duct. Patients were followed-up with telephone interviews and on an outpatient basis. Technical success was 100% for both groups. Minor early complications were noticed in 13.3% of the bare stent group and 10% of the patients of the covered stent group. The mean follow-up period was 212 days (45-675 days) and all patients had passed away at the end of the study. Thirty-day mortality was zero for both groups. Median survival time was 180.5 days for the bare stents and 243.5 days for the covered stents, withp<0.05. Stent’s mean patency rate was 166 days for the mesh stent and 227.3 days for the covered stent, withp<0.05. Stent dysfunction occurred in 9 patients with bare stent after a mean period of 133.1 days and forceps biopsy revealed ingrowth in 88.8%. Dysfunction occurred also in 4 cases of the covered stent group after a mean period of 179.5 days and it was due to tumour overgrowth in 2 and due to sludge incrustation in another 2. Tumour ingrowth occurred exclusively in the mesh stent group. There was also no difference in the overall cost of the two groups after a cost analysis.

The second prospective randomised trial that compared ePTFE/FEP covered stents with bare stents was performed in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma and revealed similar results [37]. The study was performed in 80 patients that were also randomised with the use of a sealed envelope into a bare stent and a covered stent group. The patients were 53 men and 27 women with an age range from 41 to 79 years (mean 62.7 years). Technical success was 100% in both groups. Early complications were observed in 10% of the bare and 12.5% of the covered stent group. Median follow-up time was 192 days (range of 104-603 days); all patients passed away by the end of the study. The 30-day mortality was zero for both groups. Median survival time was 203.2 days for the bare stent group and 247 days for the covered stent group, and this difference was not statistically significant. Mean primary patency was 166 days for the uncovered and 234 days for the covered stents, with p< 0.05. Dysfunction occurred in 12 bare stents after a mean period of 82.9 days and it was due to tumour ingrowth in 91.6% of the cases. Dysfunction occurred in 4 covered stents after a mean period of 126.5 days and it was due to tumour overgrowth in 2 and due to sludge in 2. Cost analysis revealed that there was no difference in the overall cost of the two groups. The two randomised trials showed that the ePTFE/FEP covered metal stents appear to reduce significantly the rate of stent’s dysfunction. The micro porous membrane appears to limit completely the risk of tumour ingrowth, which is the main issue of the use of metallic endoprosthesis in malignant biliary obstruction. However, in order to benefit from the results of covered stents patient’s survival needs to be long enough for ingrowth to occur. If survival of more than six months can be predicted -by the lack of metastatic disease and the performance status of the patients- then use of an ePTFE/FEP-covered stent is completely justified. The mentioned device appears to limit also another of the major problems of the covered stents which is stents’ migration, by having the lateral barbs (anchoring fins).

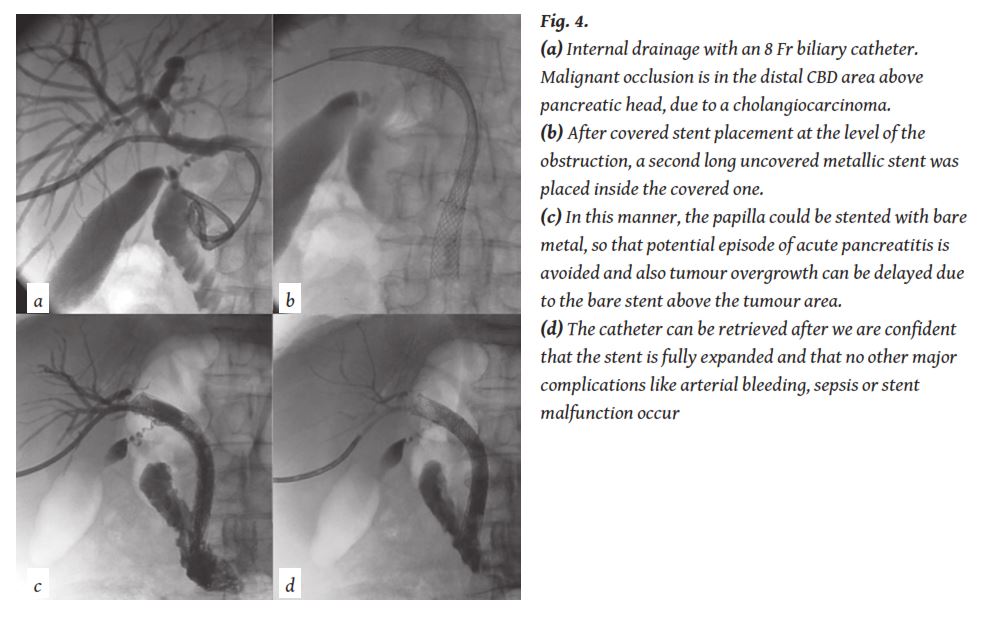

There are still some investigations going on about prevention of “overgrowth”. An improvement might be achieved if covered stent placement could be combined with bare stent extension proximal and distal to the coverage. In this manner, the papilla could be stented with bare metal, so that potential episode of acute pancreatitis is avoided and also tumour overgrowth can be delayed due to the bare stent above the tumour area (

The decision on whether to obtain an endoscopic or a percutaneous access to a blocked biliary system has been based mainly on local expertise and availability. There is very limited comparison of the two approaches in the literature. The area where the two methods have been more extensively compared is the preoperative biliary drainage where the endoscopic approach is considered to jeopardise the aseptic biliary environment and lead to infections of patients that will be operated. The existing studies have been analysed in a very recently published meta- analysis with a focus on patients with resectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma [48]. The authors included four retrospective studies on 433 patients; 275 (63.5%) underwent an endoscopic drainage and 158 (36.5%) a percutaneous. The percutaneous approach has demonstrated to offer superior results in terms of procedure-related morbidity and rate of conversion from one procedure to the other and cholangitis rate whereas pancreatitis occurred exclusively in the endoscopic group.

In a very recent publication the results of EUS are compared with the use of percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographic endobiliary forceps biopsy (PTC-EFB) in termsof diagnostic samples performance in 137 patients in a retrospective cohort study showing similar sensitivity, negative predictive value and accuracy [49]. The authors concluded that endobiliary biopsy should be the treatment of choice in case biliary drainage is also required.

The most common minor complications are pain, stent migration, stent insufficient expansion and fever. Pain is treated or prevented by IV or IM administration of analgesics and/or sedatives [41]. Stent insufficient expansion can be corrected by post-stenting balloon dilatation. Stent misplacement or migration can be corrected by placement of a second stent.

Most feared major complications are sepsis, bleeding and bile leakage. As mentioned above, complication rate within the first 30 days is about 2%, while late complications rate can reach 16% [23]. Comparing uncovered to covered stents, minor early complications were noticed in 10-13.3% of the bare stent group and 10-12.5% of the patients of the covered stent group, with a 30-day mortality of 0% for both groups [37, 38].

In order to prevent such serious complications, biliary interventions should be performed under IV antibiotic coverage [50]. Any biliary intervention is considered at the minimum a clean-contaminated procedure and therefore the recommendation is that all patients scheduled for biliary drainage receive prophylactic antibiotics prior to the procedure [50-52]. Transient bacteraemia occurs in approximately 2% of patients after biliary intervention [51]. If a patient develops fever and/or chills following biliary intervention, antibiotics may be continued, fluid resuscitation should be initiated and the need for blood cultures considered. In some cases, infection does not respond to these measures and additional drainage may be required to address incompletely drained or isolated bile segments. In patients with sub-segmental isolation, multiple drains could potentially be required and long-term antibiotic suppression may be favoured [52].

Arterial bleeding is a relatively rare complication of PTBD, appearing in 0.6-2.3% and when it does not resolve spontaneously, it should be treated by selective arterial embolisation [53-55]. Arterial complications might be prevented by obtaining access from second or third order ducts, located in the periphery of the liver and not near the hilum. Central punctures might be complicated with portal vein and/or arterial injury that will be manifested with haemobilia and/or pseudoaneurysm formation. It appears that there is a higher incidence of haemobilia associated with left lobe puncture, but did not reach the threshold of statistical significance (p=0.077) in previous studies [56, 57]. An emergency angiography should be considered in all patients in whom a pseudoaneurysm is suspected following hepatobiliary interventions. Transcatheter arterial coil embolisation is a safe and effective treatment for pseudoaneurysm with a technical success rate of 95.8% [57, 58]. Minor complications can be observed after embolisation in 80.6% patients, 76.4% of whom may have hepatic ischaemia and 4.2% focal hepatic infarction [57]. Surgical intervention should be reserved for patients for whom embolisation is not possible or fails [59].

Bile leakage can occur through the parenchymal tract after catheter removal

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary procedures are integrated in the management of patients with MBOs. In case of operable disease preoperative biliary drainage may be performed - with better results than the endoscopic approach- offering decompression of the biliary tree and access for endobiliary biopsy. In case of palliative approach either woven bare stents or covered stents may be used to alleviate jaundice for the patient’s life span. Such procedures have to be part of the everyday armamentarium of interventional radiology centres. Future perspectives will probably be in the direction of smaller profile and functional (or “drug eluting”) stents and endobiliary ablation treatment that are still in a very ear

1.Wade TP, Prasad CN, Virgo KS, et al. Experience with distal bile duct cancers in U.S. Veterans Affairs hospitals: 1987-1991.J Surg Oncol1997; 64: 242-245.

2.Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Lin E, et al. Outcome of treatment for distal bile duct cancer.Br J Surg1996; 83: 1712-1715.

3.Krokidis M, Hatzidakis A. Percutaneous minimally invasive treatment of malignant biliary strictures: Current status.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2014; 37(2): 316-323.

4.Assimakopoulos SF, Scopa CD, Vagianos CE. Pathophysiology of increased intestinal permeability in obstructive jaundice.World J Gastroenterol2007; 13: 6458-6464.

5.Walter T, Ho CS, Horgan AM, et al. Endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage for Klatskin tumors?J Vasc Interv Radiol2013; 24(1): 113-121.

6.Kloek JJ, van der Gaag NA, Aziz Y, et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous preoperative biliary drainage in patients with suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma.J Gastrointest Surg2010; 14(1): 119-125.

7.Pancreatic Section, British Society of Gastroenterology, Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland, Royal College of Pathologists, Special Interest Group for Gastro-intestinal Radiology. Guidelines for the management of patients with pancreatic cancer periampullary and ampullary carcinomas.Gut2005; 54 (suppl 5): v1–v16.

8.Lacomis JM, Baron RL, Oliver JH, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: Delayed CT contrast enhancement patterns.Radiology1997; 203: 98-104.

9.Guibaud L, Bret PM, Reinhold C, et al. Bile duct obstruction and choledocholithiasis: Diagnosis with MR cholangiography.Radiology1995; 197: 109- 115.

10.Bismuth H, Corlette MB. Intrahepatic cholangioenteric anastomosis in carcinoma of the hilus of the liver.Surg Gynecol Obstet1975; 140: 170-178.

11.Okuda K, Tanikawa K, Emura T, et al. Nonsurgical, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography-diagnostic significance in medical problems of the liver.Am J Dig Dis1974; 19(1): 21-36.

12.Bismuth H, Castaing D, Traynor O. Resection or palliation: Priority of surgery in the treatment of hilar cancer.World J Surg1988; 12(1): 39-47.

13.Nilsson U, Evander A, Ihse I, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and drainage.Risks and complications.Acta Radiol Diagn(Stockh) 1983; 24(6): 433-439.

14.Hatzidakis A, Adam A. The interventional radiological management of cholangio-carcinoma.Clinical Radiology2003; 58: 91-96.

15.Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Sriram PVJ, et al. EUSguided fine-needle cytodiagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case series.Gastrointest Endosc2000; 52: 534-540.

16.De Bellis M, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. Tissue sampling at ERCP in suspected malignant biliary strictures (part 2).Gastrointest Endosc2002; 56: 720-730.

17.Park JG, Jung GS, Yun JH, et al. Percutaneous transluminal forceps biopsy in patients suspected of having malignant biliary obstruction: factors influencing the outcomes of 271 patients.Eur Radiol 2017; 27. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-4796-x. [Epub ahead of print]

18.Adam A. Metallic biliary endoprostheses.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol1994; 17: 127-132.

19.Rossi P, Bezzi M, Rossi M, et al. Metallic stents in malignant biliary obstruction: Results of a Multicenter European Study of 240 patients.J Vasc Interv Radiol1994; 5: 279-285.

20.Hatzidakis A, Tsetis D, Chrysou E, et al. Nitinol stents for palliative treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice. Should we stent the sphincter of Oddi in every case?Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2001; 24: 245-248.

21.Lammer J, Hausegger KA, Flückiger F, et al. Common bile duct obstruction due to malignancy: Treatment with plasticversusmetal stents.Radiology1996; 201(1): 167-172.

22.Brountzos EN, Ptochis N, Panagiotou I, et al. A survival analysis of patients with malignant biliary strictures treated by percutaneous metallic stenting.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2007; 30:66-73.

23.Kaskarelis IS, Papadaki MG, Papageorgiou GN, et al. Long-term follow-up in patients with malignant biliary obstruction after percutaneous placement of uncovered wallstent endoprostheses.Acta Radiol1999; 40: 528-533.

24.Hatzidakis A, Krokidis M, Kalbakis K, et al. ePTFE/ FEP-covered metallic stents for palliation of malignant biliary disease: can tumor ingrowth be prevented?Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2007; 30(5): 950-958.

25.Hausegger KA, Kleinert R, Lammer J, et al. Biliary obstruction: Histologic findings after treatment with self-expandable stents.Radiology1992; 185: 461-464.

26.Boguth L, Tatalovic S, Antonucci F, et al. Malignant biliary obstruction: Clinical and histopathologic correlation after treatment with self-expanding metal prostheses.Radiology1994; 192: 669-674.

27.Krokidis M, Hatzidakis A. ePTFE/FEP covered metal stents in malignant biliary disease. In: Fanelli F (ed). Biliary Disease and Advanced Therapies using ePTFE/ FEP Covered Stents.Minerva Medica Turin2014: 23-38.

28.Saito H, Sakurai Y, Takamura A, et al. Biliary endoprosthesis using Gore Tex covered expandable metallic stents: Preliminary clinical evaluation. [Article in Japanese].Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi1994; 54(2): 180-182.

29.Thurnher SA, Lammer J, Thurnher MM, et al. Covered self-expanding transhepatic biliary stents: Clinical pilot study.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol1996; 19: 10-14.

30.Rossi P, Bezzi M, Salvatori FM, et al. Clinical experience with covered Wallstents for biliary malignancies: 23-month follow-up.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol1997; 20: 441-447.

31.Hausegger KA, Thurnher S, Bodendorfer G, et al. Treatment of malignant biliary obstruction with polyurethane covered Wallstents.AJR Am J Roentgenol1998; 170(2): 403-408.

32.Kanasaki S, Furukawa A, Kane T, et al. Polyurethane-covered nitinol Strecker stents as primary palliative treatment of malignant biliary obstruction.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2000; 23: 114-120.

33.Miyayama S, Matsui O, Terayama T, et al. Covered Gianturco stents for malignant biliary obstruction: Preliminary clinical evaluation.J Vasc Interv Radiol1997; 8: 641-648.

34.Han YM, Jin GY, Lee S, et al. Flared Polyurethane-covered Self expandable Nitinol Stent for Malignant Biliary Obstruction.J Vasc Interv Radiol2003; 14: 1291-1301.

35.Isayama H, Komatsu Y, Tsujino T, et al. Polyurethane-covered metal stent for management of distal malignant biliary obstruction.Gastrointest Endosc2002; 55: 366-370.

36.Isayama H, Komatsu Y, Tsujino T, et al. A prospective randomized study of “covered”vs.“uncovered” diamond stents for the management of distal malignant biliary obstruction.Gut2004; 53: 729-734.

37.Krokidis M, Fanelli F, Orgera G, et al. Percutaneous palliation of pancreatic head cancer: Randomized comparison of ePTFE/FEP-coveredvs.uncovered nitinol biliary stents.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2011; 34(2): 352-361.

38.Krokidis M, Fanelli F, Orgera G, et al. Percutaneous treatment of malignant jaundice due to extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Covered Viabil stentvs.uncovered Wallstents.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2010; 33: 97-106.

39.Krokidis M, Orgera G, Fanelli F, et al. Covered biliary metal stents: Which, where, when?Gastrointest Endosc2011; 74(5): 173-1174.

40.Adam A, Chetty N, Roddie M, et al. Self-expandable stainless steel endoprostheses for treatment of malignant bile duct obstruction.AJR Am J Roentgenol1991; 156(2): 321-325.

41.Hatzidakis AA, Charonitakis E, Athanasiou A, et al. Sedation and analgesia in patients undergoing percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.Clin Radiol2003; 58(2): 121-127.

42.Inal M, Akgul E, Seydaoglu G. Percutaneous placement of biliary metallic stents in patients with malignant hilar obstruction: Unilobarvs.bilobar drainage.J Vasc Interv Radiol2003;14: 1409-1416.

43.Li M, Wu W, Yin Z, et al. Unilateralversusbilateral biliary drainage for malignant hilar obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. [Article in Chinese]Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi2015; 23(2): 118-123.

44.De Palma GD, Galloro G, Siciliano S, et al. Unilateral versus bilateral endoscopic hepatic duct drainage in patients with malignant hilar biliary obstruction: Results of a prospective, randomized, and controlled study.Gastrointest Endosc2001; 53(6): 547-553.

45.Gamanagatti S, Singh T, Sharma R et al. Unilobar Versus Bilobar Biliary Drainage: Effect on Quality of Life and Bilirubin Level Reduction.Indian J Palliat Care2016; 22(1): 50-62.

46.Moss AC, Morris E, Leyden J, et al. Do the benefits of metal stents justify the costs? A systematic review and meta-analysis of trials comparing endoscopic stents for malignant biliary obstruction.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol2007; 19(12): 1119-1124.

47.Hong WD, Chen XW, Wu WZ, et al. Metalvs.plastic stents for malignant biliary obstruction: An update meta-analysis.Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol2013; 37(5): 496-500.

48.Al Mahjoub A, Menahem B, Fohlen A, et al. Preoperative Biliary Drainage in Patients with Resectable Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Is Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage Safer and More Effective than Endoscopic Biliary Drainage? A Meta-Analysis.J Vasc Interv Radiol2017; 28(4): 576-582.

49.Mohkam K, Malik Y, Derosas C, et al. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiographic endobiliary forceps biopsy versus endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration for proximal biliary strictures: A single-centre experience.HPB (Oxford)2017; Mar 13. pii: S1365- 182X(17)30066-7. doi: 10.1016/j.hpb.2017.02.001. [Epub ahead of print]

50.Huang SY, Philip A, Richter MD, et al. Prevention and management of infectious complications of percutaneous interventions.Semin Intervent Radiol2015; 32(2): 78-88.

51.Venkatesan AM, Kundu S, Sacks D, et al. Practice guidelines for adult antibiotic prophylaxis during vascular and interventional radiology procedures. Written by the Standards of Practice Committee for the Society of Interventional Radiology and Endorsed by the Cardiovascular Interventional Radiological Society of Europe and Canadian Interventional Radiology Association.J Vasc Interv Radiol2010; 21: 1611-1630.

52.Brody LA, Brown KT, Getrajdman GI, et al. Clinical factors associated with positive bile cultures during primary percutaneous biliary drainage.J Vasc Interv Radiol1998; 9: 572-578.

53.Winick AB, Waybill PN, Venbrux AC. Complications of percutaneous transhepatic biliary interventions.Tech Vasc Interv Radiol2001;4: 200-206.

54.Yarmohammadi H and Covey AM. Percutaneous biliary interventions and complications in malignant bile duct obstruction.Chin Clin Oncol2016; 5(5): 68-78.

55.L’Hermine C, Ernst O, Delemazure O, et al. Arterial complications of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol1996; 19(3): 160-164.

56.Rivera-Sanfeliz GM, Assar OS, LaBerge JM, et al. Incidence of important hemobilia following transhepatic biliary drainage: Left-sidedvs.right-sided approaches.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2004; 27(2): 137-139.

57.Choi SH, Gwon DI, Ko GY, et al. Hepatic Arterial Injuries in 3110 Patients Following Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage.Radiology2011; 261(3): 969-975.

58.Marynissen T, Maleux G, Heye S, et al. Transcatheter arterial embolization for iatrogenic hemobilia is a safe and effective procedure: Case series and review of the literature.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol2012; 24: 905-909.

59.Tsai CC, Chiu KC, Mo LR, et al. Transcatheter arterial coil embolization of iatrogenic pseudoaneurysms after hepatobiliary and pancreatic interventions.Hepatogastroenterology2007; 54(73): 41-46.

60.Dale AP, Khan R, Mathew A, et al. Hepatic tract embolization after biliary stenting. Is it worthwhile?Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol2015; 38(5): 1244-1251.

61.Uller W, Mueller-Wille R, Grothues D, et al. Gelfoam for closure of large percutaneous transhepatic and transsplenic puncture tracts in pediatric patients.Rofo2014; 186(7): 693-697.

62.Park SY, Kim J, Kim BW, et al. Embolization of percutaneous transhepatic portal venous access tract with N-butyl cyanoacrylate.Br J Radiol2014; 87: 20140347.

None