This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

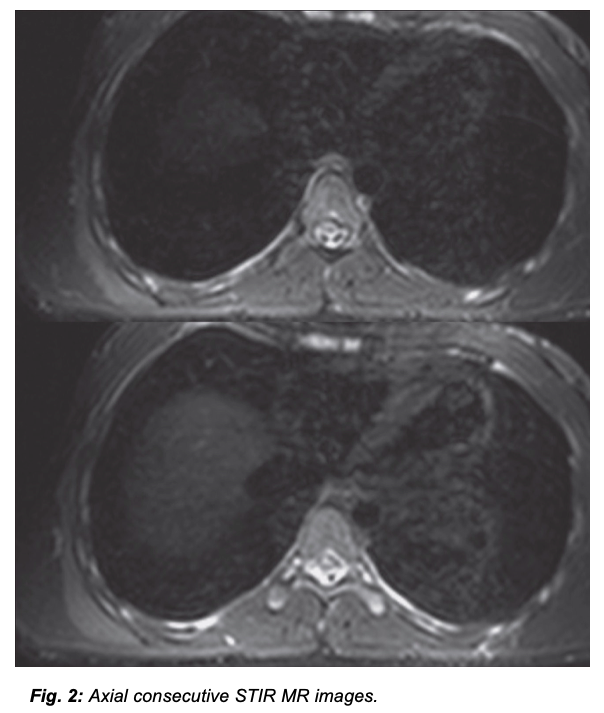

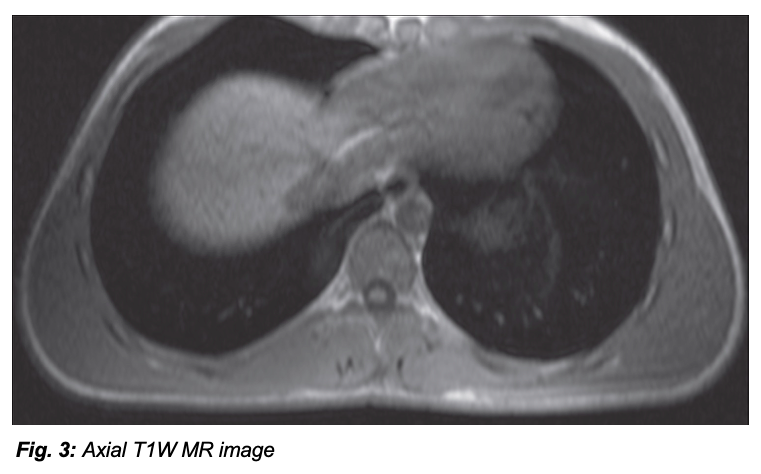

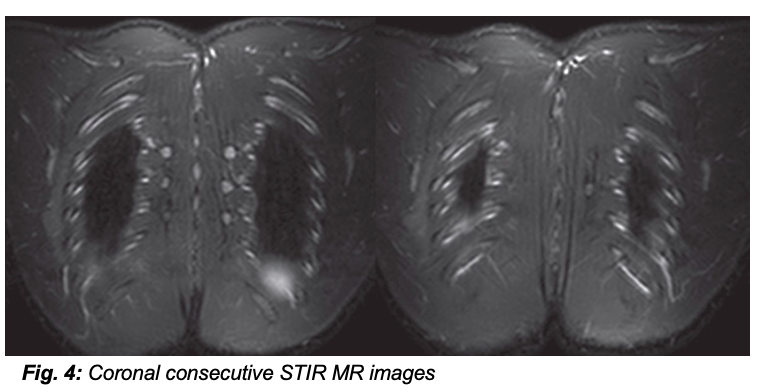

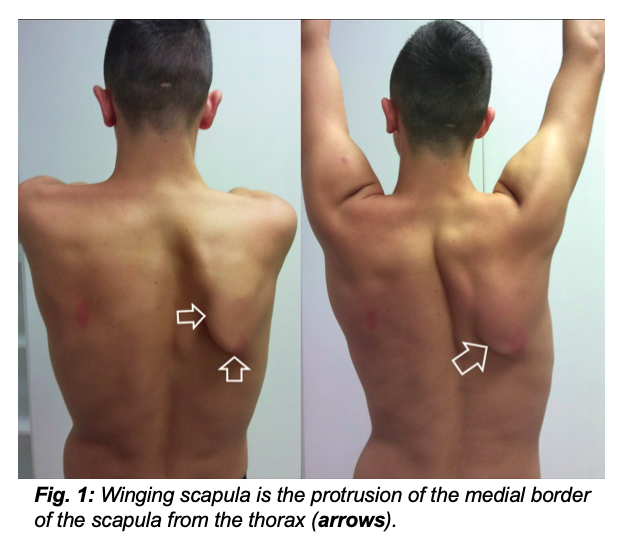

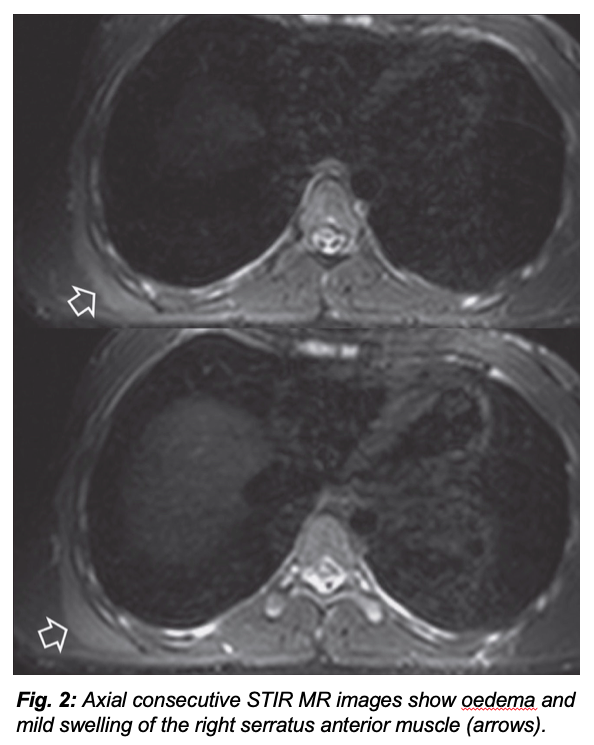

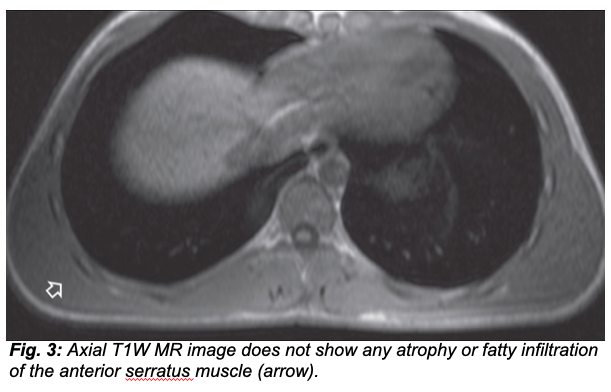

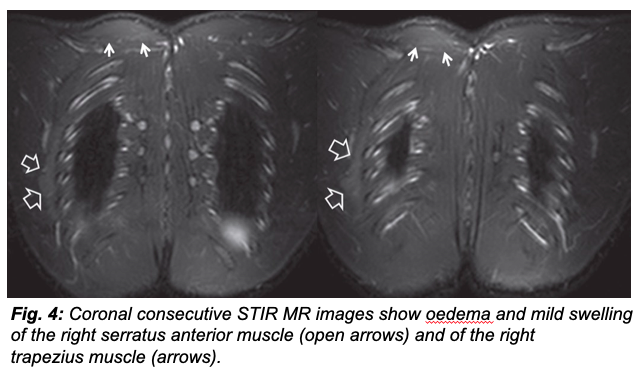

A 17-year-old male patient, elite track athlete, presented with a winging scapula (Fig. 1). His past medical history revealed a right arm pain lasting for a period of two weeks, two months before presentation. Clinical findings included slight impairment of biceps and right brachioradialis reflexes, as well as right serratus muscle weakness. An electromyography study (EMG) was performed. Axial STIR (Fig. 2), axial T1W (Fig. 3) and coronal STIR (Fig. 4) magnetic resonance (MR) images are shown.

A 17-year-old male

patient, elite track athlete, presented with a winging scapula (

PART B

Winging scapula is defined as

the wing-like appearance of the medial scapular border and may result from

various pathologies related to long thoracic nerve injury and serratus

anterior muscle paresis (

Clinically, PTs presents with acute, severe neurogenic pain in the shoulder or arm lasting for days or weeks. Pain is often unrelenting; it worsens with shoulder movements and can also worsen at night, awaking patients from sleep [4, 7]. It is often described as constant, sharp, stabbing, throbbing, or aching pain. Characteristically it is located in the shoulder and often radiates into the arm or neck, commonly aggravated by movement of the shoulder but not typically by movement of the neck or Valsalva maneuvers [7]. Pain is usually followed by muscle weakness, atrophy, paraesthesia and hypoaesthesia. Muscle weakness typically begins to develop days to weeks after the onset of pain and often worsens as the pain subsides [4, 7]. The initial pain location does not necessarily correlate to the muscle weakness distribution and does not always correlate with a single nerve root distribution. Multiple muscles may be involved which do not coincide with a single or specific nerve affliction. Upper brachial plexus involvement is the most common pattern [4]. Atrophy of the involved muscles usually occurs relatively quickly [7]. Hypoaesthesia and paraesthesia are the most commonly described sensory symptoms and the sensory loss is often patchy in distribution, corresponding to the sites of plexus or nerve involvement [4]. Autonomic symptoms have rarely been described, including trophic skin changes, oedema in the involved extremity, temperature dysregulation, changes in nail or hair growth and increased sweating [4, 7].

The diagnosis of PTs is mainly clinical but no specific tests exist. Therefore, as PTs could be confused with other diseases, such as neoplastic plexopathy, imaging is required for accurate diagnosis, which will guide proper treatment. There is no surgical treatment for PTs. Analgesics and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs along with physiotherapy usually result in full recovery within three years with a low percentage of relapse. Imaging is important in order to exclude common disorders, such as denervation from ganglion cysts or other mass-like lesions [4]. MR imaging is the method of choice, by revealing, on fluid-sensitive sequences, diffusely increased signal in various muscles in the early stages. Inchronic disease, atrophy, demonstratedwith reduction in muscle bulk and increased T1 signal due to fatty infiltration are shown. Intramuscular signal may return to normal several months after symptom onset but cases with atrophy and fatty infiltration correspond to irreversible changes [4]. EMG testing is also useful, revealing acute denervation in various muscles [3]. In our patient, full recovery was observed on the three-months clinical follow up and thus there was no need for further imaging.

1. Gooding BW, Geoghegan JM, Wallace WA, et al. Scapular winging. Shoulder Elbow 2014; 6(1): 4-11.

2. Zara G, Gasparotti R, Manara R. MR imaging of peripheral nervous system involvement: Parsonage-Turner Syndrome. J Neurol Sci 2012; 315(1-2): 170-171.

3. Bencardino JT, Rosenberg ZS. Entrapment neuropathies of the shoulder and elbow in the athlete. Clin Sports Med 2006; 25(3): 465-487.

4. Stutz CM. Neuralgic amyotrophy: Parsonage-Turner syndrome. J Hand Surg Am 2010; 35(12): 2104-2106.

5. Yanny S, Toms AP. MR patterns of denervation around the shoulder. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010; 195(2): W157-163.

6. Scalf RE, Wenger DE, Frick MA, et al. MRI findings of 26 patients with Parsonage-Turner syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007; 189(1): W39-44.

7. Smith CC, Bevelaqua AC. Challenging pain syndromes: Parsonage-Turner syndrome. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2014; 25(2): 265-277.

None