This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip is a broad term covering a wide spectrum of hip joint disorders, rang¬ing from maturation deficits to severe dysplasia or dis¬location. Published prevalence of the disorder ranges from 0.25% to 2.5% or even more in certain geograph¬ic areas. Risk factors do exist and include female gen¬der, white race, positive family history and mechan¬ical restriction during or after birth. Low sensitivity and specificity of clinical examination promoted the development of several sonographic techniques for early diagnosis. Among the above-mentioned tech¬niques, Graf’s technique, supported by extended literature and epidemiological data, offers an ana¬tomically based description of pathology and effec¬tive monitoring of treatment. Universal sonographic screening early in life is strongly recommended and initiation of treatment as early as possible is manda¬tory for an optimal outcome.

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) is a condition that includes a wide spectrum of disorders, which share the potential of causing significant long-term complications that may lead to severe disability during early adult life.

Most of the cases of DDH are potentially reversible if diagnosed and treated early. Therefore, the role of imaging, which is the mainstay of early diagnosis, is critical. Especially ultrasonography (US), the imaging modality of choice, has evolved to be the one-stop-shop imaging method for early diagnosis of DDH and the preferred tool for treatment evaluation and monitoring.

In this manuscript, we sought to review the published literature, focus on the pros and cons of US, present current clinical practice and propose an algorithm for screening.

DDH is the term which has replaced congenital dislocation of the hip in medical literature. This is mainly because it covers a wider spectrum of disorders, ranging from maturation deficits to severe dysplasia or dislocation [1, 2]. Moreover, it better describes a condition with a poorly understood natural history, the origin of which is both congenital and developmental.

The existence of various approaches to infant hip assessment, some of them being clinical and others being imaging (mainly sonographic with various techniques), makes the effort of defining pathology even more complicated, leading to several variations [2]. Fortunately, with the use of US, the exact anatomy of the infant hip joint has nowadays been studied thoroughly, facilitating a systematic approach to the joint disorders.

The definition of DDH does not include hip joint disorders which are due to co-existing medical conditions (cerebral palsy, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Legg- Calve-Perthes disease etc.), teratologic disorders and cases of traumatic hip dislocations [3, 4].

Depending on whether we refer to the pre- or the post-sonographic screening era, prevalence of DDH in the literature ranges from 0.07% to 0.15% and 0.25% to 2.5% (or even higher in certain geographic areas) respectively [3, 5, 6]. Significant geographic variability is due to true population differences, but also due to the definition variations mentioned above [7-9]. In most DDH cases, up to 80% in published reports, the disorder affects the left hip joint. This has been attributed to fetal positioning (left occiput anterior), with the left side of the fetus being more restricted and adducted as it is adjacent to the maternal sacrum, especially during the 3d trimester of pregnancy [10]. More important than the exact prevalence of the disorder is the fact that almost 1/3 of total hip replacements in patients younger than 60 are due to undiagnosed or untreated cases of DDH [11], most of which (95-98%) might have the chance of being treated if diagnosed earlier.

Risk factors according to the literature [12-15] include female gender, white race and positive family history of DDH. Mechanical restriction during pregnancy (oligohydramnios, breech presentation, macrosomic babies), during delivery (vaginal birth in breech presentation with extended legs) or after birth (swaddling), significantly contribute to morbidity. On the contrary, lack of mechanical charge explains lower incidence of DDH in premature babies. Presence of risk factors alerts the clinician to perform a thorough clinical/imaging examination, although most of the DDH cases are diagnosed in babies without any identifiable risk factors. So, it is clear that DDH screening based solely on risk factor identification is not justified [2, 16].

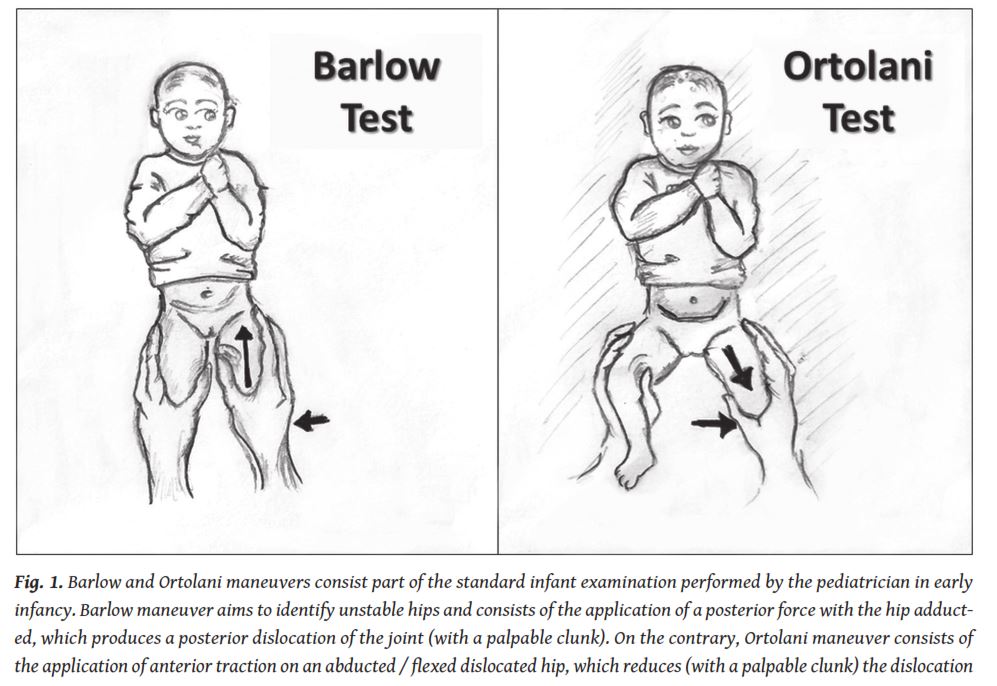

Physical examination of the hips is the initial step of hip assessment. It is usually carried out at birth by the neonatologist and subsequently routinely by the paediatrician [17]. Clinical examination mainly consists of provocative tests (namely Ortolani and Barlow (

Although it remains the mainstay of screening in several health systems and guidelines, it is neither specific nor sensitive and requires careful consideration and clinical experience [18, 19]. Dysplastic hips may remain clinically silent when the femoral head is centered [20, 21]. Even cases of severe hip dysplasia may remain clinically obscure [12, 21, 22]. The combination of risk factors and clinical history may perform slightly better; however, it is still insufficient to provide an effective screening method.

US offers us the opportunity to image the non-ossific(-ied) parts of the hip joint very early in life. Cartilaginous structures (femoral head, cartilaginous roof, labrum), joint capsule and the muscles are adequately examined with US, both in an anatomic and dynamic (when needed) way (

At the same time, integrity and adequacy of the acetabular bony roof is assessed, both qualitatively and quantitatively, and the position of the femoral head within the joint socket is documented. Several different sonographic techniques have been developed and clinically assessed, a few of which are still in clinical practice [23-27]. X-ray nowadays has a historical role in DDH screening and is preserved mainly for late presenting cases and treatment monitoring when US is no more technically feasible [28]. CT and MRI still have a role when examining the consequences of neglected or maltreated cases of DDH or when planning hip surgery [29].

The era of hip US began in 1980 when Reinhard Graf published the original paper about hip US for the diagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip in infants [23]. Over the next years, several publications suggested modifications or advances of this technique, or different techniques altogether. Traditionally, examination techniques have been categorised according to their imaging focus (acetabular morphology, femoral head coverage) or their technical approach (static vs. dynamic). It is beyond the scope of this paper to describe every different sonographic technique that is or has been used or proposed. It is our aim to emphasise the main advantages and disadvantages of the most widely used ones and then conclude with evidence based conclusions / recommendations.

Measuring the femoral head coverage (FHC), from a technical point of view, seems to be the easiest and more reproducible way to assess a hip joint. On a standard coronal hip scan the percentage of the femoral head covered by the acetabular roof is calculated as demonstrated on the figure (

There are however certain methodological problems that significantly reduce the value of the technique, which was originally proposed by Morin (USA) and Terjesen (Norway) [25, 26] and is still utilised in Northern Europe. Ovoid shape (and not spherical) of the femoral head [30], alongside with failure to define a standard plane for measurement, makes the method vulnerable to rotational distortions. Furthermore, the classification scheme utilised for assessment has a wide “gray” zone (FHC<50% may be abnormal) and an unsound reasoning behind it. As a result, it is of limited use, restricted in certain geographic areas [31].

Dynamic assessment of the hip joint was introduced by Harcke and coworkers in USA and mirrored the hypothesis that correct development of the acetabulum was heavily dependent on the position of the femoral head [24, 32]. Examination includes static and dynamic evaluation of hip stability in two examination planes (coronal and transverse) with the baby lying supine or lateral, and the hip in both neutral and flexed position (dynamic four-step method). A modified Harcke technique (including an optional rough assessment of the acetabular morphology and femoral head coverage) is the technique currently proposed by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, developed in conjunction with the American College of Radiology, the Society for Paediatric Radiology and the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound [33].

The main drawbacks of the aforementioned “dynamic” examination techniques are the following: Examination methodology (free hand, not fixed baby position) may cause certain technical problems with image acquisition, consisting mainly of rotational / tilting effects that may remain undetected (due to limited scanning plane definition) and may heavily affect image diagnostic quality and interpretation. Examination in a transverse plane does not offer any additional information and does not solve any diagnostic problems. Furthermore, qualitative interpretation of the examination results and the proposed simplified hip joint classification may be a cause of concern when following up hip treatment and a cause of subjectiveness of the results, especially when comparing the results of different examiners. Arbitrary (or on demand) addition of extra examination bits (including acetabular assessment and femoral head coverage) is not acceptable for a universal screening test which must follow a strict examination protocol. Finally, the dynamic part of the sonographic examination may be very uncomfortable and irritating for the baby (if not hazardous under certain circumstances), is not justified in the majority of cases where acetabular morphology is normal (a high correlation has been shown between acetabular morphology and hip stability in several publications) and hip instability is not separated objectively from harmless movements.

The technique that is utilised in most European countries is Graf’s technique. The main advantage of this technique is that it offers a well-structured anatomical approach, based on the application of a stepwise, strictly defined protocol (

The addition of specified checklists for the examiner helps in avoiding certain technical mistakes and further enhances correct interpretation and classification in certain categories. The examination is carried out in the lateral position using an examination cradle with a fixed probe guide. This setting is considered a necessary adjunct for correct image acquisition and maintenance of a standard examination plane. Image acquisition is followed by anatomical identification. The acquired image is only acceptable for diagnosis if it depicts certain anatomic structures. If any of them is missing, then it is considered unacceptable and a new image must be acquired (

Usability check follows anatomic identification. As already mentioned, it is absolutely necessary to define a standard plane of examination, because only then can the examiner be confident that the image is correctly acquired, lines and angles can be drawn and the examination is appropriate for clinical judgment. For this purpose, a standardised approach is utilised (lower limb-plane-labrum) to define the correct scanning position and plane (

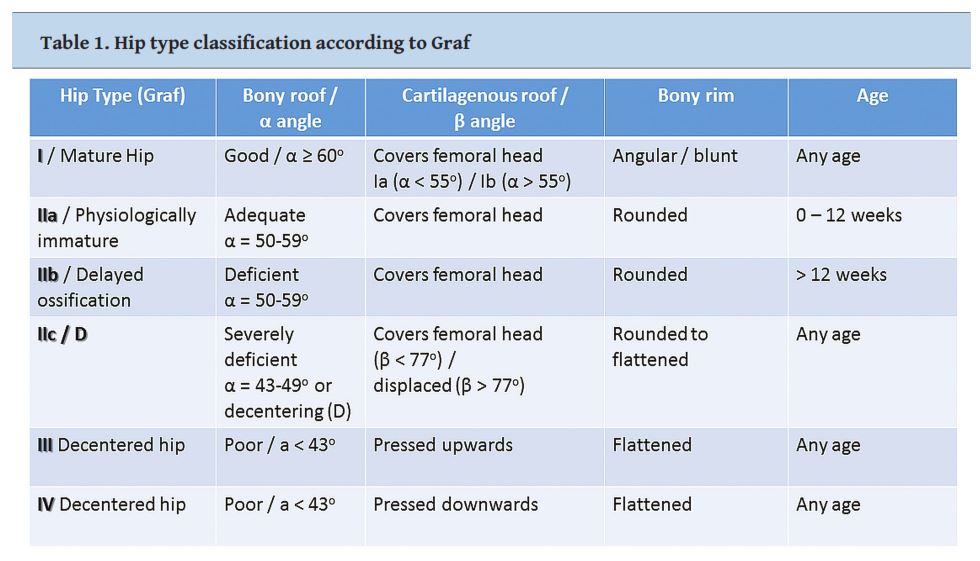

Provided that a correct image at a standard scanning plane has been acquired, morphological classification into four main categories (I to IV) is then performed and comprises the first step of the interpretation of the scan (

Fig. 7a (above), 7b (below).Provided that a correct image at a standard scanning plane has been acquired, morphological classification into four main categories (I to IV) is then performed. This comprises the first step of the interpretation of the scan

Hip examination and type classification is performed in a resting position (without stress). A dynamic examination is only preserved for a specific hip joint category(ΙΙc). In those cases, separating harmless movements from (pathological) instability is important for treatment decisions. The same examination protocol and hip type categorisation is also used for treatment monitoring. Strict adherence to the above-mentioned examination steps (correct baby positioning, anatomic identification, usability check etc.) eliminates the risk of mistakes. However, there are cases where poor examination technique, no usability check, wrong anatomic identification or incorrect measurements have led to misdiagnoses.

Graf’s examination technique’s main criticism is about its complexity. This is mainly due to the fact that it no longer uses the original clinical and x-ray classification of normal, dysplastic, subluxed and dislocated hip, but classifies hip joints according to the exact anatomic pathology which must be identified and treated appropriately. What is considered by many the main disadvantage of the technique is actually its main strength: on the basis of this classification, treatment can be conducted appropriately according to the exact sonographic hip type. Monitoring of treatment is much easier and more objective since evaluation is no longer qualitative [34].

Although universal clinical screening has been common clinical practice for many decades, universal hip screening has not gained general approval [2, 35]. The reason for this is mainly the fact that there is wide geographic variation in screening policies, published literature is heterogeneous (screening methods and population composition differ in different studies) and there are no randomised trials (it is not ethical to perform any). The fact that there are different diagnostic definitions for DDH further complicates the situation. Thus, at least at firstsight, it seems impossible to collect high quality evidence to support universal sonographic screening.

On the other hand, in Austria and Germany, universal population screening with US is being carried out since the 1990’s and there is sufficient epidemiological data to support it [35-37]. Dramatic decrease of treatment costs and surgical intervention rates in young patients with DDH were shown (

A significant number of publications which are critical of Graf’s technique, supporting clinical over sonographic screening for DDH, exhibit images which are suboptimal and thus non-diagnostic (according to the stepwise examination protocol presented above). This further supports the attitude that high quality hip US is not always available and proves that training has not been as optimal as desired. Erroneous US diagnoses are common and are mainly due to suboptimal technique. According to Graf, bedside teaching by non-authorized teachers must be rejected because it promotes habitual faults being passed on [38, 39]. Continuous advancement of hip US necessitates extra tuition of instructors. Thus, it is mandatory, in parallel with the screening policy, to adequately train the examiners and maintain a high level of competence by a carefully designed certification and audit scheme.

Appropriate US screening time has been a matter of debate. Maturation of the hip joint (measured as an increase of theαangle), is more rapid during the first few months of life [40]. Therefore, scanning babies as early as possible is important in order to achieve the best results of treatment, if needed. To eliminate unnecessary re-examinations, it would be reasonable to perform US screening early enough to provide the best possible outcome in treated cases, while at the same time offering an appropriate time window for the spontaneous resolution of immature hips. Performing a scan during the first week of life in clinically unstable hips or high-risk cases and screening all babies between the fourth and sixth week might be an optimal screening protocol [41]. However, any policy that would involve universal US screening until the second month at the latest would be sufficient.

Selection of the appropriate screening scenario is heavily dependent on local or national circumstances [37, 38] and the aim would be to ascertain that all babies would be scanned at some time during the first weeks of life.

DDH treatment aims at (1) centering the head within the acetabulum to facilitate correct development of the former, thus preventing future limping and (2) eliminating acetabular dysplasia, thus preventing early onset of arthritis and the need of early arthroplasty in a young adult. Treatment algorithm consists of femoral head reduction, maintenance of head relocation (retention) and correction of any residual acetabular dysplasia (maturation).

There is still some controversy about the correct timing of initiation of treatment (especially head reduction). There is some concern that reduction maneuvers should be performed after the ossification nucleus appears, in order to avoid head necrosis. According to the majority of published reports, early initiation of treatment is suggested.

The key in reduction technique is flexing the hips at 110owith a maximum abduction of 45o. Correct positioning is of utmost importance, to avoid causing avascular necrosis of the femoral head due to exertion of excessive pressure on the centered head.

Treatment of dislocated or unstable dysplastic hips consists of:

femoral head reduction: in babies younger than 6 months, early (as soon as possible) closed reduction of the femoral head / in older babies, open reduction (except when the femoral head is relocating easily),

application of a spica cast for 4-6 weeks (retention), although in newborns some centers may use the Pavlik harness,

depending on the age of the baby, a Pavlik harness is used until the hip joint turns to a Graf Type I hip (maturation) or until the baby is too old for a Pavlik or other flexion - abduction device (or plaster). If there is a residual dysplasia, a pelvic osteotomy is arranged at the age of 2 years or later.

In stable (centered) dysplastic hips, therapy begins from the maturation step (c).

US offers an effective and accurate method for the early diagnosis of DDH. Among the most popular sonographic techniques, Graf’s technique is a powerful screening tool which is based on anatomical description of hip pathology, and combines early diagnosis with effective monitoring of treatment. Its universal application for more than two decades in central European countries has been clinically useful and thus it is generally recommended. Timing of screening should be modified according to regional peculiarities. It is however mandatory that diagnosis should not be made later than eight weeks to ensure early initiation of treatment. The treatment algorithm consists of femoral head reduction, maintenance of head relocation (retention) and correction of any residual acetabular dysplasia.

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

1.Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip.Lancet2007; 369: 1541-1552.

2.Shipman SA, Helfand M, Moyer VA, et al. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: A systematic literature review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.Pediatrics2006; 117(3): e557-576.

3.Bialik V, Bialik GM, Blazer S, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: A new approach to incidence.Pediatrics1999; 103(1): 93-99.

4.Nemeth BA, Narotam V. Developmental Dysplasia of the hip.Pediatr Rev2012; 33(12): 553-561.

5.Patel H; Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health C. Preventive health care, 2001 update: Screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns.CMAJ2001; 164: 1669-1677.

6.American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Clinical practice guideline: Early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip.Pediatrics2000; 105: 896-905.

7.Haasbeek JF, Wright JG, Hedden DM. Is there a difference between the epidemiologic characteristics of hip dislocation diagnosed early and late?Can J Surg1995; 38: 437-438.

8.Kremli MK, Alshahid AH, Khoshhal KI, et al. The pattern of developmental dysplasia of the hip.Saudi Med J2003; 24: 1118-1120.

9.Kutlu A, Memik R, Mutlu M, et al. Congenital dislocation of the hip and its relation to swaddling used in Turkey.J Pediatr Orthop1992; 12(5): 598-602.

10.Aronsson DD, Goldberg MJ, Kling TF Jr., et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip.Pediatr1994; 94: 201-208.

11.Sewell MD, Rosendahl K, Eastwood DM. Developmental dysplasia of the hip.BMJ2009; 339: 1242-1248.

12.Bache CE, Clegg J, Herron M. Risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip: Ultrasonographic findings in the neonatal period.J Pediatr Orthop B2002; 11: 212-218.

13.Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, et al. Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip.Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed1997; 76: F94-100.

14.Yiv BC, Saidin R, Cundy PJ, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip in South Australia in 1991: Prevalence and risk factors.J Paediatr Child Health1997; 33: 151-156.

15.Stevenson DA, Mineau G, Kerber RA, et al. Familial predisposition to developmental dysplasia of the hip.J Pediatr Orthop2009; 29: 463-466.

16.Standing Medical Advisory Committee. Screening for the detection of congenital dislocation of the hip.Arch Dis Child1986; 61: 921-926.

17.Bracken J, Ditchfield M. Ultrasonography in developmental dysplasia of the hip: What have we learned?Pediatr Radiol2012; 42(12): 1418-1431.

18.Bialik V, Fishman J, Katzir J, et al. Clinical assessment of hip instability in the newborn by an orthopedic surgeon and a pediatrician.J Ped Orthop1986; 6 (6): 703-705.

19.Finne PH, Dalen I, Ikonomou N, et al. Diagnosis of congenital hip dysplasia in the newborn.Acta Orthopaedica2008; 79(3): 313-320.

20.Dogruel H, Atalar H, Yavuz OY, et al. Clinical examinationversusultrasonography in detecting developmental dysplasia of the hip.Int Orthop2008; 32(3): 415-419.

21.Kowalczyk B, Felus J, Kwinta P. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: the problems in the diagnosis process in our own experience.Med Wieku Rozwoj2005; 9(3 Pt 1): 395-406.

22.Feluś J, Kowalczyk B. Clinicaly silent developmental hip dysplasia - significancy of the hip ultrasonographic examination.Chir Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol2005; 70(6): 397-400.

23.Graf R. The diagnosis of congenital hip-joint dislocation by the ultrasonic Combound treatment.Arch Orthop Trauma Surg1980; 97: 117-133.

24.Harcke HT, Clarke NM, Lee MS, et al. Examination of the infant hip with real-time ultrasonography.JUltrasound Med1984; 3: 131-137.

25.Morin C, Harcke HT, MacEwen GD. The infant hip: Realtime US assessment of acetabular development.Radiology1985; 157: 673-677.

26.Terjesen T, Bredland T, Berg V. Ultrasound for hip assessment in the newborn.J Bone Joint Surg Br1989; 71: 767–773.

27.Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound in the early diagnosis of congenital dislocation of the hip: the significance of hip stabilityversusacetabular morphology.Pediatr Radiol1992; 22: 430-433.

28.28.Graf R. Hip Sonography. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg2006, pp 14-26.

29.29.Starr V, Ha BY. Imaging Update on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip With the Role of MRI.AJR Am J Roengenol2014; 203: 1324-1335.

30.30.Lopes D, Neptune RR, Gonçalves AA, et al. Shape analysis of the femoral head: A comparative study between spherical, (super)ellipsoidal, and (super)ovoidal Shapes.J Biomech Eng2015 Nov;137(11):114504. doi: 10.1115/1.4031650.

31.Rosendahl K, Toma P. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. The European approach. A review of methods, accuracy and clinical validity.Eur Radiol2007; 17:1960-1967.

32.Harcke HT, Grissom LE. Performing dynamic sonography of the infant hip.AJR Am J Roengenol1990; 155: 837-844.

33.National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). Guideline summary: ACR Appropriateness Criteria® developmental dysplasia of the hip-child. In: National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC). Available via https:// www.guideline.gov/summaries/summary/47675/ acr-appropriateness-criteria--developmental-dysplasia-of-the-hip---child?q=Subluxation+of+joint. Published March 29, 2006. Updated February 27, 2014. Accessed September 17, 2016.

34.Dorn U, Neumann D. Ultrasound for screening developmental dysplasia of the hip: a European perspective.Curr Opin Pediatr2005; 17(1): 30-33.

35.Graf R, Tschauner C, Klapsch W. Progress in prevention of late developmental dislocation of the hip by sonographic newborn hip “screening”: Results of a comparative follow-up study.J Pediatr Orthop B1993; 2: 115-121.

36.Riboni G, Bellini A, Serantoni S, et al. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip.Pediatr Radiol2003; 33: 475-481.

37.Toma P, Valle M, Rossi U, et al. Paediatric hip - ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: A review.Eur J Ultrasound2001; 14: 45-55.

38.Riccabona M, Schweintzger G, Grill F. Screening for developmental hip dysplasia (DDH)-clinically or sonographically? Comments to the current discussion and proposals.Pediatr Radiol2013; 43: 637-640.

39.Graf R, Mohajer M, Plattner F. Hip sonography update. Quality –management, catastrophes– tips and tricks.Med Ultrason2013; 15: 299-303.

40.Graf R. Hip Sonography. Springer-Verlag,Berlin Heidelberg2006; 83-93.

41.Farr S, Grill F, Müller D. When is the optimal time for hip ultrasound screening? [Article in German].Orthopäde2008; 37(6): 532-540.

None